Baron von Steuben Quote

Related Quotes

Nowadays, a simple faulty brake light traffic stop, can get a black person killed. It's better to fix the broken light bulb, then having to face and cooperate with a senseless police officer.

Anthony Liccione

Tags:

african american, america, black, blacklivesmatter, citizen, come to terms, come together, death, equality, fatal

Unfortunately, the board of directors that the middle managers report to generally make them aggressive. Imagine being hired into a company and then being told that you have to ignore the emerging hea...

Steven Magee

Tags:

activities, aggressive, america, board, company, corporate, dangerous, directors, emerging, engage

There is coming a day, when freedom will just be a essence of the mind, an inner dwelling that was once physically attainable. They will tell you where you can live, and what you can wear and drive, w...

Anthony Liccione

Tags:

abolish, after the rapture, age, america, antichrist, authority, bird, brainwash, buy and sell, cage

About Baron von Steuben

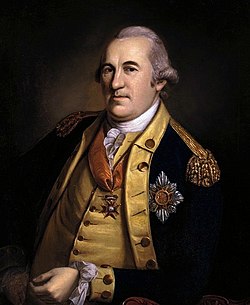

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand Freiherr von Steuben ( STEW-bən or stew-BEN, German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈvɪlhɛlm fɔn ˈʃtɔʏbn̩]; born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis Freiherr von Steuben; September 17, 1730 – November 28, 1794), also referred to as Baron von Steuben, was a German-born American army officer who played a leading role in the American Revolutionary War by reforming the Continental Army into a disciplined and professional fighting force. His contributions marked a significant improvement in the performance of U.S. troops.

Born into a military family, Steuben was exposed to war from an early age; at 14 years old, he observed his father directing Prussian engineers in the 1744 siege of Prague. At age 16 or 17, he enlisted in the Prussian Army, which was considered the most professional and disciplined in Europe. During his 17 years of military service, Steuben took part in several battles in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), rose to the rank of captain, and became aide-de-camp to King Frederick II of Prussia, who was renowned for his military prowess and strategy. Steuben's career culminated in his attendance of Frederick's elite school for young military officers, after which he was abruptly discharged from the army in 1763, allegedly by the machinations of a rival.

Steuben spent 11 years as court chamberlain to the prince of Hohenzollern-Hechingen, a small German principality. In 1769, the Duchess of Wurttemberg, a niece of Frederick, named him to the chivalric Order of Fidelity, a meritorious award that conferred the title Freiherr, or 'free lord'; in 1771, his service to Hohenzollern-Hechingen earned him the title baron. In 1775, as the American Revolution had begun, Steuben saw a reduction in his salary and sought some form of military work; unable to find employment in peacetime Europe, he joined the U.S. war effort through mutual French contacts with U.S. diplomats, most notably ambassadors to France Silas Deane and Benjamin Franklin. Due to his military exploits, and his willingness to serve the Americans without compensation, Steuben made a positive impression on both Congress and General George Washington, who appointed him as temporary Inspector General of the Continental Army.

Appalled by the state of U.S. forces, Steuben took the lead in teaching soldiers the essentials of military drills, tactics, and discipline based on Prussian techniques. He wrote Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States, which remained the army's drill manual for decades, and continues to influence modern U.S. army manuals. Steuben also addressed widespread administrative waste and graft, helping save desperately needed supplies and funds. As these reforms began bearing fruit on the battlefield, in 1778, Congress, on Washington's recommendation, commissioned Steuben to the position of Inspector General with the rank of Major General. He served the remainder of the war as Washington's chief of staff and one of his most trusted advisors.

After the war, Steuben was made a U.S. citizen and granted a large estate in New York in reward for his service. In 1780, he was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society, a learned society that included many of the nation's most prominent Founding Fathers.

Born into a military family, Steuben was exposed to war from an early age; at 14 years old, he observed his father directing Prussian engineers in the 1744 siege of Prague. At age 16 or 17, he enlisted in the Prussian Army, which was considered the most professional and disciplined in Europe. During his 17 years of military service, Steuben took part in several battles in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), rose to the rank of captain, and became aide-de-camp to King Frederick II of Prussia, who was renowned for his military prowess and strategy. Steuben's career culminated in his attendance of Frederick's elite school for young military officers, after which he was abruptly discharged from the army in 1763, allegedly by the machinations of a rival.

Steuben spent 11 years as court chamberlain to the prince of Hohenzollern-Hechingen, a small German principality. In 1769, the Duchess of Wurttemberg, a niece of Frederick, named him to the chivalric Order of Fidelity, a meritorious award that conferred the title Freiherr, or 'free lord'; in 1771, his service to Hohenzollern-Hechingen earned him the title baron. In 1775, as the American Revolution had begun, Steuben saw a reduction in his salary and sought some form of military work; unable to find employment in peacetime Europe, he joined the U.S. war effort through mutual French contacts with U.S. diplomats, most notably ambassadors to France Silas Deane and Benjamin Franklin. Due to his military exploits, and his willingness to serve the Americans without compensation, Steuben made a positive impression on both Congress and General George Washington, who appointed him as temporary Inspector General of the Continental Army.

Appalled by the state of U.S. forces, Steuben took the lead in teaching soldiers the essentials of military drills, tactics, and discipline based on Prussian techniques. He wrote Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States, which remained the army's drill manual for decades, and continues to influence modern U.S. army manuals. Steuben also addressed widespread administrative waste and graft, helping save desperately needed supplies and funds. As these reforms began bearing fruit on the battlefield, in 1778, Congress, on Washington's recommendation, commissioned Steuben to the position of Inspector General with the rank of Major General. He served the remainder of the war as Washington's chief of staff and one of his most trusted advisors.

After the war, Steuben was made a U.S. citizen and granted a large estate in New York in reward for his service. In 1780, he was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society, a learned society that included many of the nation's most prominent Founding Fathers.